Douglas Max Utter talks to Fred Bidwell about the Transformer Station

24/12/12

Plugged In

By Douglas Max Utter

“Nobody’s ever—kind of—done this before…” Fred Bidwell glances distractedly through his office windows. Outside, the square brick façade of the Bidwell Foundation’s new Transformer Station renovation and expansion can be seen directly across West 29th Street – the “this” that he’s talking about.

I think he means the qualifying phrase “kind of” as a disclaimer. But in fact nobody has done it before, or at least it’s safe to say there’s never been anything else in Cleveland that very much resembled it. Maybe Bidwell’s reticence is a telltale sign of his Boston upbringing, surfacing at the far end of a very successful career in advertising in the Akron area.

Fred Bidwell and Laura Ruth Bidwell

But bragging would be fine. After all, very few people take it into their heads to start a museum. And in this case it will be a museum of world class contemporary art, with an emphasis on cutting edge photography – and admission will be free. It’s an impressive gift to the people and to the public life of northern Ohio, one that echoes the largess of the city’s past, when the area’s great art institutions were founded and funded through the remarkable generosity of locally-based entrepreneurs like Leonard C. Hanna.

“Why did we do this?” Bidwell is still sitting at his desk, gazing out at the bunker-like building surrounded by construction debris. It looks less than welcoming just now, in the cold morning light of a late October day. “Everyone’s been very lattering and attributed all kinds of high-minded motives to us. But really it’s pretty selfish. We wanted to have a place to show our collection. It was getting to the point where things were just going directly into storage. And also, we want to do things that will be fulfilling for us. There’s a difference between art in the home and art in a museum.”

Exposing the work to new audiences can be like discovering it all over again. “You see life in a totally different way through someone else’s eyes.” He’s thinking here of his collecting partner Laura, whose upstairs office is presently under construction at the new museum. They’ve been married for more than two decades, having met in the early 1990s at the advertising agency where both worked. “It was an office romance,” Fred remarks with wry warmth.

Apparently their tastes and passions for art also dovetail pretty well. “Laura was a painting major at Kent State University. I was an art history major at Oberlin, and I spent years trying to make it as a fine art photographer.” They both loved photography and enjoyed collecting for all the reasons that collectors do: acquiring beautiful, interesting things, of course, but also participating in the energies generated by a vital international art scene. “It made sense to focus on something. And at the time photography was very reasonably priced.”

Matthew Brandt, Big Bear, 2012, Photograph

So, the simple storyline is that many, many photographic acquisitions later, the unassuming couple buys a solid old building with walls of medieval thickness (the 1924 structure was built to house the transformer that powered the nearby Detroit Avenue trolleys, adhering to specs that could withstand a catastrophic explosion), and turns it into a museum to highlight and share their acquisitions. But those who keep track of the northern Ohio art scene have seen this unassuming “power” duo do a lot more than just buy art, however important that is. Both the Akron Art Museum and the Cleveland Museum of Art have benefited from Bidwell funding and projects. A couple of years ago New York photographer Andrew Moore’s epic studies of failed industries’ ruined towers and throne rooms in the Detroit area (some insensitive types have called work in this genre “ruin porn,” but actual porn was never so beautiful or mysterious) were financed by the Bidwells and shown in the Akron Museum’s moving “Detroit Disassembled” show.

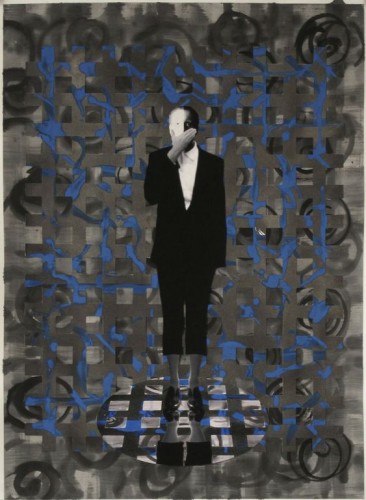

Nor are the photographs that they acquire necessarily recognizable as such. Some, like Ohio artist Don Harvey’s recent “Mime,” are hybrids resulting from a lifetime’s worth of cross-fertilization between painting and photography that transcend either medium. Or there’s Los Angeles photographer Matthew Brandt’s mural-sized color landscape shot of a mountain lake. The point is not the photo itself, so much as the damage and changes that occurred after it was soaked in the lake that it depicted, plus the beauty of those accidental stains and marks and the overarching contradictions of identity that they suggest. An almost philosophical excitement underlies the Bidwell’s collecting impulse, reflecting the core impulses of contemporary art itself. “We like to buy things that are brand new,” he remarks, pretending for a minute to be crass. “What I would call “art futures.” But it’s far from crass to vote for the future.

Don Harvey, Mime, 2012, oil and collage on paper, 2012

Architect John C. Williams located the building and designed an addition, after the Cleveland Museum of Art’s new Director David Franklin learned of the project and offered to partner with the Bidwells. Identical in height and square footage to the original structure, the new gray stone annex is plugged into the back of the old Transformer Station, deliberately echoing the granite façade of CMA’s 1971 Marcel Breuer addition. Over the next 15-20 years CMA will split programming initiatives with the Bidwell Foundation, eventually inheriting both the building and much of the Bidwells’ collection in a package estimated to be worth around $7.5 million. “We may keep going for the full twenty years, or until it stops being fun. At that point they can sell it or do whatever they want with it,” chuckles Bidwell. Among the benefits for both CMA and the city is the fact that the museum will have a functioning branch on the west side of town for the first time. The growing west side gallery scene—including the Lakewood-based Cleveland Artists Foundation exhibition space at the Beck Center and the burgeoning Gordon Square Arts District, with its rapidly growing audiences—will gain a new, world-class facility.

A very large, industrial strength hook hangs from a mighty chain inside Transformer Station. It’s too iconic—and maybe too heavy—to get rid of. And anyway it reminds visitors of the area’s history as it adds a slightly scary moment of visual intrigue to the building’s interior. Visitors who see it after the museum opens in February will immediately recognize that this is one museum that doesn’t really need any more of a hook.