Plain Dealer on Art and Innovation

17/09/17

Cleveland's new views on innovation find expression in art, architecture: PD 175

By Steven Litt, The Plain Dealer

CLEVELAND, Ohio - A century ago, Cleveland's industrial magnates saw art and architecture as sources of pleasure or signifiers of wealth and status - not as fonts of inspiration for creativity and innovation in business.

Today, it's different. At least some business and nonprofit leaders in Northeast Ohio see strong parallels between innovation in arts and culture and in business. And they're changing the city, and the arts.

The most visible embodiment of the trend is cultural entrepreneur Fred Bidwell, the retired advertising executive who's masterminding the FRONT International Cleveland Triennial, a summer-long exhibition of global, national and local art that will debut in Cleveland in 2018.

FRONT, a citywide art exhibit with global reach, will debut in Cleveland in 2018 (photos)

A new nonprofit group in Cleveland announced the launch of FRONT, a global triennial art exhibition that will debut in the summer of 2018.

Ad man aims to rebrand city

The goal of the nonprofit project is to rebrand Cleveland as a must-visit global venue for contemporary art and as a place that embraces cutting edge creative thinking in business as well as the arts.

"Being involved in the arts and creativity is all about encouraging an attitude of innovation that goes beyond the arts," Bidwell said. "Creativity should pervade everything and innovation should pervade everything, whether you're an accountant or a painter."

Bidwell's vision is not without local precedent.

Peter B. Lewis, leader of Mayfield-based Progressive Corp., who died in 2013 at age 80, earned a global reputation for his patronage of Frank Gehry, one of the world's most famous and innovative architects. Lewis fell in love with contemporary art during the decades in which he built his business. A budding collector, Lewis in 1983 hired his then-ex wife Toby Devan Lewis to assemble what became one of the largest and most admired corporate art collections in the U.S., focusing exclusively on contemporary work. Shaping history of architecture In the mid-1980s, Lewis encountered Gehry at the Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art, now called the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, and the two hit it off. Lewis first commissioned Gehry to design a skyscraper headquarters for Progressive on the downtown Cleveland lakefront, a project that collapsed for lack of political buy-in on the part of mayors George Voinovich and Mike White. Lewis also commissioned Gehry to design an immense and architecturally ambitious house for him in Lyndhurst that was never built because the estimated cost grew too high, even for Lewis. But Gehry later widely credited the experimentation facilitated by Lewis's support during the years he spent on the house project as having prepared him to design the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, in 1997. The Washington Post called the unbuilt project "The House That Built a Revolution." Other examples of corporate leaders who have embraced innovation in the arts include Milton Maltz, who founded Malrite Communications in 1956 and served as its chairman and CEO until he sold the company in 1998. Maltz then launched Malrite Co., which developed innovative entertainment and museum projects including the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage in Beachwood. Dealer Tire CEO Scott Mueller is an enthusiastic collector of contemporary art who donated $20 million to the capital campaign that funded the Cleveland Museum of Art's recent $320 million expansion and renovation. Art, architecture and healthcare And outgoing Cleveland Clinic CEO Toby Cosgrove oversaw billions of dollars worth of construction at the Clinic's main campus, regional satellites and new complex in Abu Dhabi that embraced a lean, minimalist brand of contemporary architecture. At the Cleveland headquarters, Cosgrove enabled the creation of a large and ambitious collection of contemporary art through the Clinic's Arts & Medicine Foundation. The enthusiasm shown by these leaders for crossover understandings of innovation in the arts, business and medicine stands in contrast with attitudes during the city's industrial heyday.

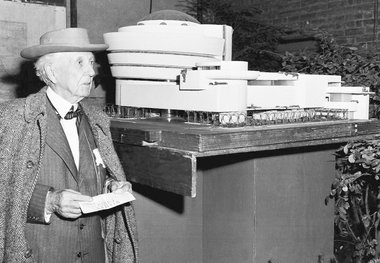

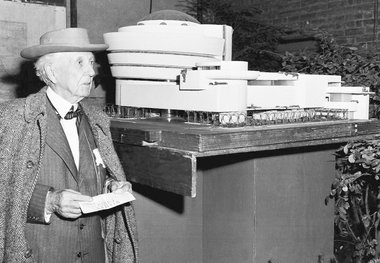

The city's tycoons patronized the arts, leaving legacies that include the Cleveland Orchestra and the Cleveland Museum of Art. But their tastes were conservative, rather than aligned with the avant-garde. The question is whether those conservative inclinations related in some way to the city's long decline starting during the Depression and the postwar years. Is there a link between innovation and entrepreneurship and progressive views of the arts? Whatever one's perspective, it's clear Cleveland's artistic patrons and architectural clients viewed innovative art and design with scant enthusiasm during the city's downturn. Geniuses need not apply The industrial Great Lakes region from the early to mid-20th century was a global epicenter of architectural innovation. Yet none of the regional design geniuses of the day - from Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright of Chicago to Eliel and Eero Saarinen of Detroit, ever got a job in Cleveland.

Frank Lloyd Wright's 150th b-day a time to marvel at his work

Frank Lloyd Wright, born 150 years ago this summer, led an at times unsavory life, but his architecture transcended the man's limitations - and those of traditional architecture as well.

The same was true after World War II of German-born Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who then lived in Chicago.

Instead, the magnates of Millionaire's Row built immense mansions in backward-looking historical revival styles on Euclid Avenue, and then tore them down after fleeing encroaching industrial development and city taxes they considered too high.

Developers Oris and Mantis Van Sweringen, catering to the wealthy urban exiles, filled Shaker Heights with Tudoresque homes, captivating colonials and wannabe French chateaux.

Homegrown talents

Clevelanders are justifiably proud of homegrown architectural talents such as Frank Walker and Harry Weeks, J. Milton Dyer and Benjamin Hubbell and W. Dominick Benes, who bestowed Cleveland with its museums, concert halls and neoclassical civic buildings in its downtown Group Plan District.

Yet stylistically speaking, their buildings weren't tremendously innovative. And they haven't gained notice outside Northeast Ohio. A list of America's 150 favorite buildings compiled by the American Institute of Architects doesn't include a single entry from Cleveland.

As for the visual arts, the single most famous image to emerge from the city throughout its entire history is the kitschy and sentimental "The Spirit of '76" by Archibald Willard, originally exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial in 1876.

In New York, Chicago, Boston and Philadelphia, wealthy collectors invested heavily in modern art, which found relatively few enthusiasts in Cleveland.

Pittsburgh and Buffalo

In Pittsburgh, steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie backed the Carnegie Museum of Art's triennial international shows, which brought the best of the world's contemporary art to the city, and the museum has continued to buy works out of the show, creating a powerful collection of art from the 1890s forward.

Frank Lloyd Wright's 150th b-day a time to marvel at his work

Frank Lloyd Wright, born 150 years ago this summer, led an at times unsavory life, but his architecture transcended the man's limitations - and those of traditional architecture as well.

The same was true after World War II of German-born Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who then lived in Chicago.

Instead, the magnates of Millionaire's Row built immense mansions in backward-looking historical revival styles on Euclid Avenue, and then tore them down after fleeing encroaching industrial development and city taxes they considered too high.

Developers Oris and Mantis Van Sweringen, catering to the wealthy urban exiles, filled Shaker Heights with Tudoresque homes, captivating colonials and wannabe French chateaux.

Homegrown talents

Clevelanders are justifiably proud of homegrown architectural talents such as Frank Walker and Harry Weeks, J. Milton Dyer and Benjamin Hubbell and W. Dominick Benes, who bestowed Cleveland with its museums, concert halls and neoclassical civic buildings in its downtown Group Plan District.

Yet stylistically speaking, their buildings weren't tremendously innovative. And they haven't gained notice outside Northeast Ohio. A list of America's 150 favorite buildings compiled by the American Institute of Architects doesn't include a single entry from Cleveland.

As for the visual arts, the single most famous image to emerge from the city throughout its entire history is the kitschy and sentimental "The Spirit of '76" by Archibald Willard, originally exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial in 1876.

In New York, Chicago, Boston and Philadelphia, wealthy collectors invested heavily in modern art, which found relatively few enthusiasts in Cleveland.

Pittsburgh and Buffalo

In Pittsburgh, steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie backed the Carnegie Museum of Art's triennial international shows, which brought the best of the world's contemporary art to the city, and the museum has continued to buy works out of the show, creating a powerful collection of art from the 1890s forward.

In Buffalo, collector Seymour Knox Jr. helped mold the Albright-Knox Art Gallery into one of the nation's leading collections of modern and contemporary art. Nothing like that happened in Cleveland, where the Cleveland Museum of Art, backed by the city's wealthiest elites, generally looked askance at new art. In 1919, the museum launched an annual exhibition of contemporary art, known as the May Show, to nurture local artists. But the museum has devoted relatively little attention and space to contemporary art from outside the region, until the 1980s and '90s. Cool toward contemporary Under director Sherman Lee from 1958 to 1983, the museum focused primarily on collecting European old master paintings and Asian art. Those decades offered opportunities to buy works by members of the heroic generation of postwar American artists, including the Abstract-Expressionists. Cleveland missed those opportunities, which were grabbed instead by art museums in New York, Chicago and Buffalo. Whether that was a bad move by the Cleveland museum is debatable, given its impressive strengths in other areas. But it sent a message to the city's artists and the community that new art was to be viewed with skepticism. Pass-through city for greatest artists Perhaps as a result, Cleveland became a pass-through for the most important contemporary artists associated with its history. They lived here for a time, but moved on after finding other cities that nurtured their ambitions. The list includes the early 20th-century expressionist, Charles Burchfield; Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein; geometric abstractionistRobert Mangold; postmodern landscapist April Gornik; and Dana Schutz, whose colorful and visceral paintings of psychological fantasies have earned her a global reputation. Of that group, all except Lichtenstein studied at what is now the Cleveland Institute of Art. The two most famous visual artists associated with Cleveland, who also taught at the art institute, industrial designer Viktor Schreckengost and Op Art painter Julian Stanczak, spent their lives here to avoid the politics and distractions of bigger art markets. And their national visibility suffered as a result - not that they cared. They loved Cleveland. Roll the tape forward to 2017, and the Cleveland story looks different. Arts and neighborhood revitalization Across the city, neighborhoods including Detroit Shoreway, Ohio City,Collinwood, Tremont and Little Italy have embraced the idea that contemporary artists are vital to community and economic development.

The city has been recognized nationally for blending the arts and creative placemaking, based on examples such as Playhouse Square, which blends historic preservation of 1920s movie palaces with urban revitalization. The city is sprinkled with buildings designed by A-list contemporary architects of a type who would not have received commissions here in earlier decades. Examples include Frank Gehry, designer of the Weatherhead School of Management at Case Western Reserve University; Farshid Moussavi, designer of the new Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland; Stanley Saitowitz of San Francisco, designer of the Uptown apartments; and Rafael Vinoly, architect of the Cleveland Museum of Art's expansion and renovation. The Bidwell story As a business leader and patron of the arts, Bidwell's personal story encapsulates Northeast Ohio's recent evolution toward innovation and reinvention. A self described failed artist, Bidwell graduated from Oberlin with a bachelor's degree in art history and spent seven years attempting to become a creative photographer. He had a work accepted in the Cleveland Museum of Art's May Show, but eventually gave up his artistic ambitions. "I set my sights on the idea of working for an ad agency," he said. "It seemed like ad agencies were having all the fun, and ordering me around."

Bidwell got a job in 1982 at Malone Advertising in Akron, a medium-sized regional firm that he described as "a little bit of a dinosaur already when I joined it." Fear as motivator Malone's clients were all local, Bidwell said, and it was highly dependent on Goodyear. In 1996, the year in which Bidwell acquired controlling interest in Malone, Goodyear dropped the firm. He described the moment as "a near death experience." "I was forced to innovate by fear," he said. "It was a wakeup call. The business could never survive if it had to depend on local clients because those clients were all going away." On Bidwell's watch, Malone became a leader in "shopper marketing," which focuses on influencing consumer behavior during the experience of shopping. The transformation of Malone was a success, and WPP PLC, based in Dublin, Ireland, acquired the firm, now Geometry Global, in 2005. Bidwell left advertising in 2012, and with his wife, photographer Laura Bidwell, launched an arts foundation and purchased a streetcar transformer station at 1460 W. 29th St. in Cleveland's Ohio City neighborhood, turning it into an art gallery shared with the Cleveland Museum of Art, where Bidwell is a trustee. Taking on the whole city

The Transformer Station quickly became a key anchor in Ohio City's Hingetown area, where the Bidwells later bought the Van Roy building at 2900 Detroit Ave., turning its third floor loft into their home and selling the ground floor to the nonprofit Spaces gallery.

Spaces announces move to Hingetown's Van Rooy building, owned by Fred and Laura Bidwell (photos)

The nonprofit Spaces gallery announced it is moving to the Van Rooy Building in Ohio City's Hingetown, owned by arts entrepreneurs Fred and Laura Bidwell.

After becoming part of the arts-related revitalization that's sweeping half a dozen Cleveland neighborhoods, Bidwell thought, why not take on the entire city?

Bidwell conceived FRONT as a project that would bring scores of contemporary artists to the city from around the world to stage exhibitions at venues across Cleveland and Northeast Ohio.

Spaces announces move to Hingetown's Van Rooy building, owned by Fred and Laura Bidwell (photos)

The nonprofit Spaces gallery announced it is moving to the Van Rooy Building in Ohio City's Hingetown, owned by arts entrepreneurs Fred and Laura Bidwell.

After becoming part of the arts-related revitalization that's sweeping half a dozen Cleveland neighborhoods, Bidwell thought, why not take on the entire city?

Bidwell conceived FRONT as a project that would bring scores of contemporary artists to the city from around the world to stage exhibitions at venues across Cleveland and Northeast Ohio.

FRONT International exhibit announces artists in bid for global attention in summer of 2018 (photos)

The nonprofit FRONT International exhibit announces a roster of 57 artists from around the world who will participate in the inaugural run of the triennial show, designed to put Cleveland on the global map as a key art world destination.

In the process, he hopes, the show will "redefine the city as a cultural and intellectual hub."

It's a risky move, but the $5 million investment - of which Bidwell has raised about half - is relatively modest in relation to the intended impact.

"The different thing you've got to do is innovate," Bidwell said. "You've essentially got to reinvent yourself and your business, and, ultimately, the city."

FRONT International exhibit announces artists in bid for global attention in summer of 2018 (photos)

The nonprofit FRONT International exhibit announces a roster of 57 artists from around the world who will participate in the inaugural run of the triennial show, designed to put Cleveland on the global map as a key art world destination.

In the process, he hopes, the show will "redefine the city as a cultural and intellectual hub."

It's a risky move, but the $5 million investment - of which Bidwell has raised about half - is relatively modest in relation to the intended impact.

"The different thing you've got to do is innovate," Bidwell said. "You've essentially got to reinvent yourself and your business, and, ultimately, the city."

By Steven Litt, The Plain Dealer

CLEVELAND, Ohio - A century ago, Cleveland's industrial magnates saw art and architecture as sources of pleasure or signifiers of wealth and status - not as fonts of inspiration for creativity and innovation in business.

Today, it's different. At least some business and nonprofit leaders in Northeast Ohio see strong parallels between innovation in arts and culture and in business. And they're changing the city, and the arts.

The most visible embodiment of the trend is cultural entrepreneur Fred Bidwell, the retired advertising executive who's masterminding the FRONT International Cleveland Triennial, a summer-long exhibition of global, national and local art that will debut in Cleveland in 2018.

FRONT, a citywide art exhibit with global reach, will debut in Cleveland in 2018 (photos)

A new nonprofit group in Cleveland announced the launch of FRONT, a global triennial art exhibition that will debut in the summer of 2018.

Ad man aims to rebrand city

The goal of the nonprofit project is to rebrand Cleveland as a must-visit global venue for contemporary art and as a place that embraces cutting edge creative thinking in business as well as the arts.

"Being involved in the arts and creativity is all about encouraging an attitude of innovation that goes beyond the arts," Bidwell said. "Creativity should pervade everything and innovation should pervade everything, whether you're an accountant or a painter."

Bidwell's vision is not without local precedent.

Peter B. Lewis, leader of Mayfield-based Progressive Corp., who died in 2013 at age 80, earned a global reputation for his patronage of Frank Gehry, one of the world's most famous and innovative architects. Lewis fell in love with contemporary art during the decades in which he built his business. A budding collector, Lewis in 1983 hired his then-ex wife Toby Devan Lewis to assemble what became one of the largest and most admired corporate art collections in the U.S., focusing exclusively on contemporary work. Shaping history of architecture In the mid-1980s, Lewis encountered Gehry at the Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art, now called the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, and the two hit it off. Lewis first commissioned Gehry to design a skyscraper headquarters for Progressive on the downtown Cleveland lakefront, a project that collapsed for lack of political buy-in on the part of mayors George Voinovich and Mike White. Lewis also commissioned Gehry to design an immense and architecturally ambitious house for him in Lyndhurst that was never built because the estimated cost grew too high, even for Lewis. But Gehry later widely credited the experimentation facilitated by Lewis's support during the years he spent on the house project as having prepared him to design the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, in 1997. The Washington Post called the unbuilt project "The House That Built a Revolution." Other examples of corporate leaders who have embraced innovation in the arts include Milton Maltz, who founded Malrite Communications in 1956 and served as its chairman and CEO until he sold the company in 1998. Maltz then launched Malrite Co., which developed innovative entertainment and museum projects including the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage in Beachwood. Dealer Tire CEO Scott Mueller is an enthusiastic collector of contemporary art who donated $20 million to the capital campaign that funded the Cleveland Museum of Art's recent $320 million expansion and renovation. Art, architecture and healthcare And outgoing Cleveland Clinic CEO Toby Cosgrove oversaw billions of dollars worth of construction at the Clinic's main campus, regional satellites and new complex in Abu Dhabi that embraced a lean, minimalist brand of contemporary architecture. At the Cleveland headquarters, Cosgrove enabled the creation of a large and ambitious collection of contemporary art through the Clinic's Arts & Medicine Foundation. The enthusiasm shown by these leaders for crossover understandings of innovation in the arts, business and medicine stands in contrast with attitudes during the city's industrial heyday.

The city's tycoons patronized the arts, leaving legacies that include the Cleveland Orchestra and the Cleveland Museum of Art. But their tastes were conservative, rather than aligned with the avant-garde. The question is whether those conservative inclinations related in some way to the city's long decline starting during the Depression and the postwar years. Is there a link between innovation and entrepreneurship and progressive views of the arts? Whatever one's perspective, it's clear Cleveland's artistic patrons and architectural clients viewed innovative art and design with scant enthusiasm during the city's downturn. Geniuses need not apply The industrial Great Lakes region from the early to mid-20th century was a global epicenter of architectural innovation. Yet none of the regional design geniuses of the day - from Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright of Chicago to Eliel and Eero Saarinen of Detroit, ever got a job in Cleveland.

Frank Lloyd Wright's 150th b-day a time to marvel at his work

Frank Lloyd Wright, born 150 years ago this summer, led an at times unsavory life, but his architecture transcended the man's limitations - and those of traditional architecture as well.

The same was true after World War II of German-born Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who then lived in Chicago.

Instead, the magnates of Millionaire's Row built immense mansions in backward-looking historical revival styles on Euclid Avenue, and then tore them down after fleeing encroaching industrial development and city taxes they considered too high.

Developers Oris and Mantis Van Sweringen, catering to the wealthy urban exiles, filled Shaker Heights with Tudoresque homes, captivating colonials and wannabe French chateaux.

Homegrown talents

Clevelanders are justifiably proud of homegrown architectural talents such as Frank Walker and Harry Weeks, J. Milton Dyer and Benjamin Hubbell and W. Dominick Benes, who bestowed Cleveland with its museums, concert halls and neoclassical civic buildings in its downtown Group Plan District.

Yet stylistically speaking, their buildings weren't tremendously innovative. And they haven't gained notice outside Northeast Ohio. A list of America's 150 favorite buildings compiled by the American Institute of Architects doesn't include a single entry from Cleveland.

As for the visual arts, the single most famous image to emerge from the city throughout its entire history is the kitschy and sentimental "The Spirit of '76" by Archibald Willard, originally exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial in 1876.

In New York, Chicago, Boston and Philadelphia, wealthy collectors invested heavily in modern art, which found relatively few enthusiasts in Cleveland.

Pittsburgh and Buffalo

In Pittsburgh, steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie backed the Carnegie Museum of Art's triennial international shows, which brought the best of the world's contemporary art to the city, and the museum has continued to buy works out of the show, creating a powerful collection of art from the 1890s forward.

Frank Lloyd Wright's 150th b-day a time to marvel at his work

Frank Lloyd Wright, born 150 years ago this summer, led an at times unsavory life, but his architecture transcended the man's limitations - and those of traditional architecture as well.

The same was true after World War II of German-born Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who then lived in Chicago.

Instead, the magnates of Millionaire's Row built immense mansions in backward-looking historical revival styles on Euclid Avenue, and then tore them down after fleeing encroaching industrial development and city taxes they considered too high.

Developers Oris and Mantis Van Sweringen, catering to the wealthy urban exiles, filled Shaker Heights with Tudoresque homes, captivating colonials and wannabe French chateaux.

Homegrown talents

Clevelanders are justifiably proud of homegrown architectural talents such as Frank Walker and Harry Weeks, J. Milton Dyer and Benjamin Hubbell and W. Dominick Benes, who bestowed Cleveland with its museums, concert halls and neoclassical civic buildings in its downtown Group Plan District.

Yet stylistically speaking, their buildings weren't tremendously innovative. And they haven't gained notice outside Northeast Ohio. A list of America's 150 favorite buildings compiled by the American Institute of Architects doesn't include a single entry from Cleveland.

As for the visual arts, the single most famous image to emerge from the city throughout its entire history is the kitschy and sentimental "The Spirit of '76" by Archibald Willard, originally exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial in 1876.

In New York, Chicago, Boston and Philadelphia, wealthy collectors invested heavily in modern art, which found relatively few enthusiasts in Cleveland.

Pittsburgh and Buffalo

In Pittsburgh, steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie backed the Carnegie Museum of Art's triennial international shows, which brought the best of the world's contemporary art to the city, and the museum has continued to buy works out of the show, creating a powerful collection of art from the 1890s forward.In Buffalo, collector Seymour Knox Jr. helped mold the Albright-Knox Art Gallery into one of the nation's leading collections of modern and contemporary art. Nothing like that happened in Cleveland, where the Cleveland Museum of Art, backed by the city's wealthiest elites, generally looked askance at new art. In 1919, the museum launched an annual exhibition of contemporary art, known as the May Show, to nurture local artists. But the museum has devoted relatively little attention and space to contemporary art from outside the region, until the 1980s and '90s. Cool toward contemporary Under director Sherman Lee from 1958 to 1983, the museum focused primarily on collecting European old master paintings and Asian art. Those decades offered opportunities to buy works by members of the heroic generation of postwar American artists, including the Abstract-Expressionists. Cleveland missed those opportunities, which were grabbed instead by art museums in New York, Chicago and Buffalo. Whether that was a bad move by the Cleveland museum is debatable, given its impressive strengths in other areas. But it sent a message to the city's artists and the community that new art was to be viewed with skepticism. Pass-through city for greatest artists Perhaps as a result, Cleveland became a pass-through for the most important contemporary artists associated with its history. They lived here for a time, but moved on after finding other cities that nurtured their ambitions. The list includes the early 20th-century expressionist, Charles Burchfield; Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein; geometric abstractionistRobert Mangold; postmodern landscapist April Gornik; and Dana Schutz, whose colorful and visceral paintings of psychological fantasies have earned her a global reputation. Of that group, all except Lichtenstein studied at what is now the Cleveland Institute of Art. The two most famous visual artists associated with Cleveland, who also taught at the art institute, industrial designer Viktor Schreckengost and Op Art painter Julian Stanczak, spent their lives here to avoid the politics and distractions of bigger art markets. And their national visibility suffered as a result - not that they cared. They loved Cleveland. Roll the tape forward to 2017, and the Cleveland story looks different. Arts and neighborhood revitalization Across the city, neighborhoods including Detroit Shoreway, Ohio City,Collinwood, Tremont and Little Italy have embraced the idea that contemporary artists are vital to community and economic development.

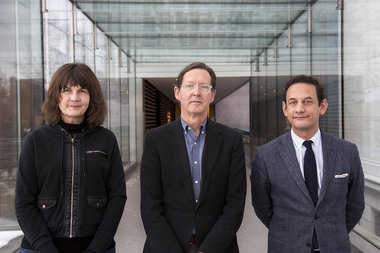

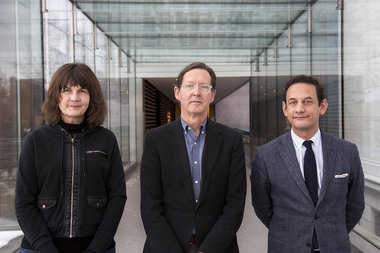

The city has been recognized nationally for blending the arts and creative placemaking, based on examples such as Playhouse Square, which blends historic preservation of 1920s movie palaces with urban revitalization. The city is sprinkled with buildings designed by A-list contemporary architects of a type who would not have received commissions here in earlier decades. Examples include Frank Gehry, designer of the Weatherhead School of Management at Case Western Reserve University; Farshid Moussavi, designer of the new Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland; Stanley Saitowitz of San Francisco, designer of the Uptown apartments; and Rafael Vinoly, architect of the Cleveland Museum of Art's expansion and renovation. The Bidwell story As a business leader and patron of the arts, Bidwell's personal story encapsulates Northeast Ohio's recent evolution toward innovation and reinvention. A self described failed artist, Bidwell graduated from Oberlin with a bachelor's degree in art history and spent seven years attempting to become a creative photographer. He had a work accepted in the Cleveland Museum of Art's May Show, but eventually gave up his artistic ambitions. "I set my sights on the idea of working for an ad agency," he said. "It seemed like ad agencies were having all the fun, and ordering me around."

Bidwell got a job in 1982 at Malone Advertising in Akron, a medium-sized regional firm that he described as "a little bit of a dinosaur already when I joined it." Fear as motivator Malone's clients were all local, Bidwell said, and it was highly dependent on Goodyear. In 1996, the year in which Bidwell acquired controlling interest in Malone, Goodyear dropped the firm. He described the moment as "a near death experience." "I was forced to innovate by fear," he said. "It was a wakeup call. The business could never survive if it had to depend on local clients because those clients were all going away." On Bidwell's watch, Malone became a leader in "shopper marketing," which focuses on influencing consumer behavior during the experience of shopping. The transformation of Malone was a success, and WPP PLC, based in Dublin, Ireland, acquired the firm, now Geometry Global, in 2005. Bidwell left advertising in 2012, and with his wife, photographer Laura Bidwell, launched an arts foundation and purchased a streetcar transformer station at 1460 W. 29th St. in Cleveland's Ohio City neighborhood, turning it into an art gallery shared with the Cleveland Museum of Art, where Bidwell is a trustee. Taking on the whole city

The Transformer Station quickly became a key anchor in Ohio City's Hingetown area, where the Bidwells later bought the Van Roy building at 2900 Detroit Ave., turning its third floor loft into their home and selling the ground floor to the nonprofit Spaces gallery.

Spaces announces move to Hingetown's Van Rooy building, owned by Fred and Laura Bidwell (photos)

The nonprofit Spaces gallery announced it is moving to the Van Rooy Building in Ohio City's Hingetown, owned by arts entrepreneurs Fred and Laura Bidwell.

After becoming part of the arts-related revitalization that's sweeping half a dozen Cleveland neighborhoods, Bidwell thought, why not take on the entire city?

Bidwell conceived FRONT as a project that would bring scores of contemporary artists to the city from around the world to stage exhibitions at venues across Cleveland and Northeast Ohio.

Spaces announces move to Hingetown's Van Rooy building, owned by Fred and Laura Bidwell (photos)

The nonprofit Spaces gallery announced it is moving to the Van Rooy Building in Ohio City's Hingetown, owned by arts entrepreneurs Fred and Laura Bidwell.

After becoming part of the arts-related revitalization that's sweeping half a dozen Cleveland neighborhoods, Bidwell thought, why not take on the entire city?

Bidwell conceived FRONT as a project that would bring scores of contemporary artists to the city from around the world to stage exhibitions at venues across Cleveland and Northeast Ohio. FRONT International exhibit announces artists in bid for global attention in summer of 2018 (photos)

The nonprofit FRONT International exhibit announces a roster of 57 artists from around the world who will participate in the inaugural run of the triennial show, designed to put Cleveland on the global map as a key art world destination.

In the process, he hopes, the show will "redefine the city as a cultural and intellectual hub."

It's a risky move, but the $5 million investment - of which Bidwell has raised about half - is relatively modest in relation to the intended impact.

"The different thing you've got to do is innovate," Bidwell said. "You've essentially got to reinvent yourself and your business, and, ultimately, the city."

FRONT International exhibit announces artists in bid for global attention in summer of 2018 (photos)

The nonprofit FRONT International exhibit announces a roster of 57 artists from around the world who will participate in the inaugural run of the triennial show, designed to put Cleveland on the global map as a key art world destination.

In the process, he hopes, the show will "redefine the city as a cultural and intellectual hub."

It's a risky move, but the $5 million investment - of which Bidwell has raised about half - is relatively modest in relation to the intended impact.

"The different thing you've got to do is innovate," Bidwell said. "You've essentially got to reinvent yourself and your business, and, ultimately, the city."