Art Hopper Reviews The Unicorn

20/11/13

Oscillating Memories: The Unicorn @ The Transformer Station

arthopper.org

November 20, 2013 by Rose Bouthillier

The Unicorn. 2013. Curated by Reto Thüring. Installation view. The Transformer Station Photo © The Cleveland Museum of Art.

The past constantly fades. Attempts to fix it in any way result in something else entirely, a skewed construct influenced by the languages, values and desires of the present.

The Unicorn, curated by Reto Thüring, takes as its premise “the difficulty, perhaps even the impossibility, of producing the past,” and features an international selection of artists: Neïl Beloufa, Martin Soto Climent, Shana Lutkner and a collaborative work by Daniel Gustav Cramer & Haris Epaminonda. The exhibition’s title is inspired by German writer Martin Walser’s novel Das Einhorn (The Unicorn, 1966), in which the protagonist, tasked with writing a novel about love, turns to his own personal history, only to realize that his experiences cannot be accurately recollected or repeated. “Our memory is a scale for losses only. A stock exchange daily accumulating losses,” he writes. The unicorn, as a mythic creature, also represents the seepage of fiction into reality, something constantly searched for but never found. While notes of nostalgia and failure permeate the exhibition, there is also a great deal of play, theatrics and discovery; loss invites new propositions.

The exhibition is the first organized at the Transformer Station by the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA), where Thüring is Associate Curator of Contemporary Art. Initiated by collectors Fred and Laura Bidwell, the Transformer Station opened in February 2013. Through a unique arrangement, it is programmed for half of the year by the departments of Contemporary Art and Photography at the CMA. The space, a renovated substation with a modernist addition, is divided into two galleries: a smaller, rougher room with vestiges of its former use, and a larger white cube. It is a bit idiosyncratic, and Thüring used the space well, fitting each project into a space that emphasizes its underlying formal concerns.

Beloufa occupies the entire smaller gallery with a video and custom installation,Untitled (2010), based on various and conflicting accounts of terrorists occupying a modernist villa in Algiers. The video takes place in a set of interiors and balconies constructed of cardboard and paper, with images of the villa itself enlarged and pasted up as backdrops. Various shadowy, anonymous figures move in and around the set. When one finally turns to face the camera, the confrontation is jolting, as if one has been caught staring, voyeuristically. The figures do not speak; the narratives playing overtop the scenes are recorded conversations Beloufa had with the villa’s owner, gardener, and others from the neighborhood.

Stills from Untitled. Neil Beloufa (French, b. 1985). 2010. HD video; 15-minute loop. © and image courtesy of the artist.

The video is projected low to the ground on one wall, while the installation fills the rest of the room with sculptures of welded steel and rough white forms. They evoke architectural remnants, modernist furniture, or a minimalist stage set—this ambiguous environment is the perfect accompaniment to the video, and is augmented by the building’s original masonry and ironwork, including a large industrial crane hanging from the ceiling. However, within this well-conceived and sensitively executed installation, the projection seems noticeably un-exact in size and framing. A strange assortment of small images are pasted to the sculptures: giraffe hide, the sky, innocuous patterns. The dimness of the room and the vague, variable shapes of the installation produce a strange sensation; when standing in the inside, it feels like one is struggling to see it entirely. After leaving the room, it is extremely difficult to recall the structure. With Untitled, Beloufa produced a complex experience that draws viewers into a mysterious, inaccessible narrative, a past whose very players are invested in its concealment.

Lukter’s stage-set like installation The Bearded Gas (2013) also takes a historical event as its starting point: La soirée du Coeur barbe (The evening of the Bearded Heart), a night of Dada performances on July 6, 1923 at the Theatre Michel in Paris. Two violent outbursts cut the event short: Andre Breton broke Pierre de Massot’s arm with his cane – a response to Massot’s slighting Pablo Picasso – and later, Paul Eluard punched playwright Tristan Tzara and actor Rene Crevel in their faces during a performance of Tzara’s Le coer à gaz (The Gas Heart). Lutker’s stage holds a cast of sculptures related to the narrative and its setting: a blown-up replica of a black star-shape form found on Breton’s grave, a tall white podium, a small set of stairs with a ladder suspended above (similar to one Lutker saw in the orchestra pit of the Theatre Michel during a research trip in 2012), and a teetering, reflective globe. The entire set is backed by a false mirrored wall, making it a lively, shifting, duplicated space, which viewers can see themselves in. At the exhibition’s opening, Lutker gave a reading accompanied by three actors, which blended accounts of the 1923 events with the artists’ own experiences and history. At one point, the actors gave a running commentary describing a Man Ray film also slated to show that violent evening, Le retour à raison (The Return to Reason, 1923), which they viewed on an iPad obscured from the audience. Familiar or not with the film, the audience was given multiple, fleeting impressions by the actors, who talked over one another at a frantic pace. Just as a rhythm set in, Lutker roughly interjected—an unscripted decision that jolted the audience out of image-imagining reverie, and the actors out from behind the third wall.

The Bearded Gas. Shana Lutker (American, b. 1978). 2013. Wood, MDF, carpet, foam core, PlexiGlas mirrors, chromed steel, paint, and wire; 168 x 216 x 144 inches. © Shana Lutker. Photo © The Cleveland Museum of Art.

The exhibition guide hosts multiple pages of Lutker’s research material: original play bills, an inexplicable IMDb entry for The Bearded Heart, hand drawn maps of Paris. This collection illustrates both Lutker’s committed approach to research and the pleasure of research’s myriad, unfolding directions. Yes, the events of 1923 are inaccessible, but they endure, scatter, and ricochet against the present. Re-discovering them, trying to get close to them, is thrilling and affirmational. The Bearded Gas offers a comical, propositional, and loose encounter with a historical moment when art was physically fought over.

À Mon Seul Désir (detail), Martin Soto Climent (Mexican, b. 1977). 2013. 108 photographs, digital prints on fine art paper; 9 x 12 inches each, overall dimensions variable. © Martin Soto Climent. Photo © The Cleveland Museum of Art.

Both Soto Climent’s À Mon Seul Désir (2013) and Cramer and Epaminonda’s The Infinite Library (2007-ongoing), take up the printed archive. Soto Climent’s title comes from a series of six tapestries known as La dame à la lincorne (The lady and the unicorn) (c. 1480-1500, Flanders). Many believe the first five represent each of the senses, while the last, inscribed with À Mon Seul Désir, presents an enigmatic scene thought to represent a “sixth sense,” an inner compass. Taking the tapestries as inspiration, Soto Climent created works using a collection of popular PHOTO magazines from the 1970s and 80s, given to the artist by his uncle and father. The images were cut out, reassembled, photographed, and then jumbled again, creating a series of echoing arrangements. The piece spreads out in multiple strands of abutting frames, across the floor and up the walls, filling a niche space in the larger gallery. While the description states that each of the strands is dedicated to one of the five senses, it is impossible to say which is which. Each uses the same types of imagery, and all seem to approach the enigmatic sixth, an inner psyche formed by experiences which cannot be broken down into discrete categories. Here, photography—a medium of sight—is presented as a nostalgic vessel that draws on desire and associative sensations. Soto Climent does not appear interested in producing any semblance of the past. Rather, À Mon Seul Désir meditates on the enduring ability of images to be a variable reflecting pool for the human psyche and personal vocabularies.

Cramer and Epaminonda’s The Infinite Library is more expansive in its source material (focusing on, but not limited to, illustrated books form 1920-1970), and much more staid in its presentation. The ongoing project consists of reconfigured books: multiple copies or different editions combined into new volumes, or all together disparate volumes mashed into freely associated pairings. Each book then becomes unfixed, unique, while the shuffling of the pages alludes to a truly endless project, multiplied by the nature of print. In an age of fast paced digital hypertext, this simplified, intertextual approach to knowledge is fantastically slow and thoughtful. The books are displayed two to a vitrine, and viewers can only contemplate the pages they are opened to—the surface of an expanding depth. The vitrines, arranged parallel in row against one wall, create the visual effect that they would go on forever, if not for the room’s containment. The Infinite Library is the most impersonal work in the show; there is no sure sense of personal encounter or the artists’ hands. It alludes to a shared unconscious, a vast, common, and sprawling repository borne out through encounter and repetition.

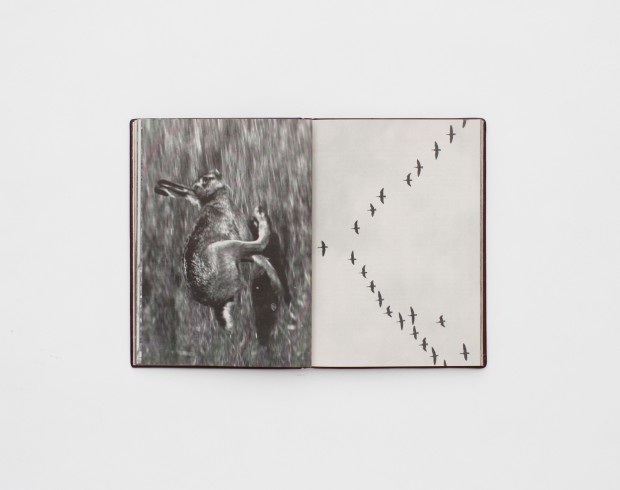

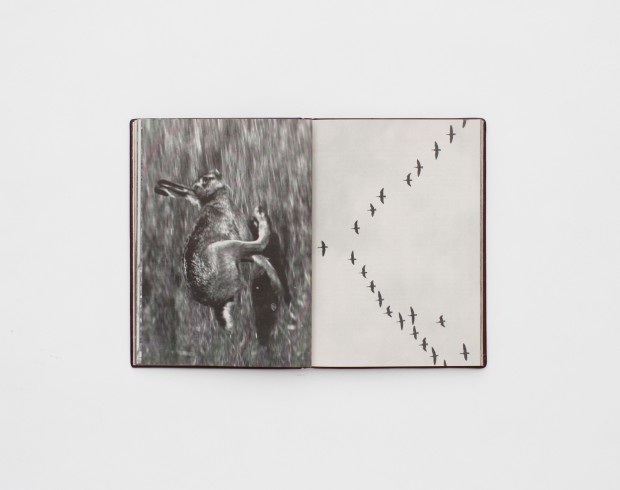

The Infinite Library, Book #24. Daniel Gustav Cramer (German, b. 1975) & Haris Epaminonda (Cypriot, b. 1980). 2011. © and image courtesy of the artists.

Looking to the past has become a central theme in contemporary art production. Art theorist Hal Foster identified “an archival impulse” in the mid 2000s, of artists looking retrieve the obscured past, in “a gesture of alternative knowledge or counter-memory.” Indeed, this thematic proliferates in a contemporary cultural landscape in which digital access makes the archive more readily available, though less authoritative. The Unicorn’s somewhat open interpretation of “the past” is not necessarily a drawback to the exhibition. Freeing the conversation from a definition of history, one focused on particular events and locations, makes for an interesting set of questions and concerns, ranging over memory, image production, and physical material. The inability to reconstruct the past is certainly a given; the works in The Unicorn do not so much explore this inability as revel in the possibilities it opens up. As the first CMA exhibition at The Transformer, The Unicorn promises exciting and challenging things to come.

Rose Bouthillier is Assistant Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland. Her writing has been published in C magazine, frieze, esse, and Art Criticism & Other Short Stories.

arthopper.org

November 20, 2013 by Rose Bouthillier

The Unicorn. 2013. Curated by Reto Thüring. Installation view. The Transformer Station Photo © The Cleveland Museum of Art.

The past constantly fades. Attempts to fix it in any way result in something else entirely, a skewed construct influenced by the languages, values and desires of the present.

The Unicorn, curated by Reto Thüring, takes as its premise “the difficulty, perhaps even the impossibility, of producing the past,” and features an international selection of artists: Neïl Beloufa, Martin Soto Climent, Shana Lutkner and a collaborative work by Daniel Gustav Cramer & Haris Epaminonda. The exhibition’s title is inspired by German writer Martin Walser’s novel Das Einhorn (The Unicorn, 1966), in which the protagonist, tasked with writing a novel about love, turns to his own personal history, only to realize that his experiences cannot be accurately recollected or repeated. “Our memory is a scale for losses only. A stock exchange daily accumulating losses,” he writes. The unicorn, as a mythic creature, also represents the seepage of fiction into reality, something constantly searched for but never found. While notes of nostalgia and failure permeate the exhibition, there is also a great deal of play, theatrics and discovery; loss invites new propositions.

The exhibition is the first organized at the Transformer Station by the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA), where Thüring is Associate Curator of Contemporary Art. Initiated by collectors Fred and Laura Bidwell, the Transformer Station opened in February 2013. Through a unique arrangement, it is programmed for half of the year by the departments of Contemporary Art and Photography at the CMA. The space, a renovated substation with a modernist addition, is divided into two galleries: a smaller, rougher room with vestiges of its former use, and a larger white cube. It is a bit idiosyncratic, and Thüring used the space well, fitting each project into a space that emphasizes its underlying formal concerns.

Beloufa occupies the entire smaller gallery with a video and custom installation,Untitled (2010), based on various and conflicting accounts of terrorists occupying a modernist villa in Algiers. The video takes place in a set of interiors and balconies constructed of cardboard and paper, with images of the villa itself enlarged and pasted up as backdrops. Various shadowy, anonymous figures move in and around the set. When one finally turns to face the camera, the confrontation is jolting, as if one has been caught staring, voyeuristically. The figures do not speak; the narratives playing overtop the scenes are recorded conversations Beloufa had with the villa’s owner, gardener, and others from the neighborhood.

Stills from Untitled. Neil Beloufa (French, b. 1985). 2010. HD video; 15-minute loop. © and image courtesy of the artist.

The video is projected low to the ground on one wall, while the installation fills the rest of the room with sculptures of welded steel and rough white forms. They evoke architectural remnants, modernist furniture, or a minimalist stage set—this ambiguous environment is the perfect accompaniment to the video, and is augmented by the building’s original masonry and ironwork, including a large industrial crane hanging from the ceiling. However, within this well-conceived and sensitively executed installation, the projection seems noticeably un-exact in size and framing. A strange assortment of small images are pasted to the sculptures: giraffe hide, the sky, innocuous patterns. The dimness of the room and the vague, variable shapes of the installation produce a strange sensation; when standing in the inside, it feels like one is struggling to see it entirely. After leaving the room, it is extremely difficult to recall the structure. With Untitled, Beloufa produced a complex experience that draws viewers into a mysterious, inaccessible narrative, a past whose very players are invested in its concealment.

Lukter’s stage-set like installation The Bearded Gas (2013) also takes a historical event as its starting point: La soirée du Coeur barbe (The evening of the Bearded Heart), a night of Dada performances on July 6, 1923 at the Theatre Michel in Paris. Two violent outbursts cut the event short: Andre Breton broke Pierre de Massot’s arm with his cane – a response to Massot’s slighting Pablo Picasso – and later, Paul Eluard punched playwright Tristan Tzara and actor Rene Crevel in their faces during a performance of Tzara’s Le coer à gaz (The Gas Heart). Lutker’s stage holds a cast of sculptures related to the narrative and its setting: a blown-up replica of a black star-shape form found on Breton’s grave, a tall white podium, a small set of stairs with a ladder suspended above (similar to one Lutker saw in the orchestra pit of the Theatre Michel during a research trip in 2012), and a teetering, reflective globe. The entire set is backed by a false mirrored wall, making it a lively, shifting, duplicated space, which viewers can see themselves in. At the exhibition’s opening, Lutker gave a reading accompanied by three actors, which blended accounts of the 1923 events with the artists’ own experiences and history. At one point, the actors gave a running commentary describing a Man Ray film also slated to show that violent evening, Le retour à raison (The Return to Reason, 1923), which they viewed on an iPad obscured from the audience. Familiar or not with the film, the audience was given multiple, fleeting impressions by the actors, who talked over one another at a frantic pace. Just as a rhythm set in, Lutker roughly interjected—an unscripted decision that jolted the audience out of image-imagining reverie, and the actors out from behind the third wall.

The Bearded Gas. Shana Lutker (American, b. 1978). 2013. Wood, MDF, carpet, foam core, PlexiGlas mirrors, chromed steel, paint, and wire; 168 x 216 x 144 inches. © Shana Lutker. Photo © The Cleveland Museum of Art.

The exhibition guide hosts multiple pages of Lutker’s research material: original play bills, an inexplicable IMDb entry for The Bearded Heart, hand drawn maps of Paris. This collection illustrates both Lutker’s committed approach to research and the pleasure of research’s myriad, unfolding directions. Yes, the events of 1923 are inaccessible, but they endure, scatter, and ricochet against the present. Re-discovering them, trying to get close to them, is thrilling and affirmational. The Bearded Gas offers a comical, propositional, and loose encounter with a historical moment when art was physically fought over.

À Mon Seul Désir (detail), Martin Soto Climent (Mexican, b. 1977). 2013. 108 photographs, digital prints on fine art paper; 9 x 12 inches each, overall dimensions variable. © Martin Soto Climent. Photo © The Cleveland Museum of Art.

Both Soto Climent’s À Mon Seul Désir (2013) and Cramer and Epaminonda’s The Infinite Library (2007-ongoing), take up the printed archive. Soto Climent’s title comes from a series of six tapestries known as La dame à la lincorne (The lady and the unicorn) (c. 1480-1500, Flanders). Many believe the first five represent each of the senses, while the last, inscribed with À Mon Seul Désir, presents an enigmatic scene thought to represent a “sixth sense,” an inner compass. Taking the tapestries as inspiration, Soto Climent created works using a collection of popular PHOTO magazines from the 1970s and 80s, given to the artist by his uncle and father. The images were cut out, reassembled, photographed, and then jumbled again, creating a series of echoing arrangements. The piece spreads out in multiple strands of abutting frames, across the floor and up the walls, filling a niche space in the larger gallery. While the description states that each of the strands is dedicated to one of the five senses, it is impossible to say which is which. Each uses the same types of imagery, and all seem to approach the enigmatic sixth, an inner psyche formed by experiences which cannot be broken down into discrete categories. Here, photography—a medium of sight—is presented as a nostalgic vessel that draws on desire and associative sensations. Soto Climent does not appear interested in producing any semblance of the past. Rather, À Mon Seul Désir meditates on the enduring ability of images to be a variable reflecting pool for the human psyche and personal vocabularies.

Cramer and Epaminonda’s The Infinite Library is more expansive in its source material (focusing on, but not limited to, illustrated books form 1920-1970), and much more staid in its presentation. The ongoing project consists of reconfigured books: multiple copies or different editions combined into new volumes, or all together disparate volumes mashed into freely associated pairings. Each book then becomes unfixed, unique, while the shuffling of the pages alludes to a truly endless project, multiplied by the nature of print. In an age of fast paced digital hypertext, this simplified, intertextual approach to knowledge is fantastically slow and thoughtful. The books are displayed two to a vitrine, and viewers can only contemplate the pages they are opened to—the surface of an expanding depth. The vitrines, arranged parallel in row against one wall, create the visual effect that they would go on forever, if not for the room’s containment. The Infinite Library is the most impersonal work in the show; there is no sure sense of personal encounter or the artists’ hands. It alludes to a shared unconscious, a vast, common, and sprawling repository borne out through encounter and repetition.

The Infinite Library, Book #24. Daniel Gustav Cramer (German, b. 1975) & Haris Epaminonda (Cypriot, b. 1980). 2011. © and image courtesy of the artists.

Looking to the past has become a central theme in contemporary art production. Art theorist Hal Foster identified “an archival impulse” in the mid 2000s, of artists looking retrieve the obscured past, in “a gesture of alternative knowledge or counter-memory.” Indeed, this thematic proliferates in a contemporary cultural landscape in which digital access makes the archive more readily available, though less authoritative. The Unicorn’s somewhat open interpretation of “the past” is not necessarily a drawback to the exhibition. Freeing the conversation from a definition of history, one focused on particular events and locations, makes for an interesting set of questions and concerns, ranging over memory, image production, and physical material. The inability to reconstruct the past is certainly a given; the works in The Unicorn do not so much explore this inability as revel in the possibilities it opens up. As the first CMA exhibition at The Transformer, The Unicorn promises exciting and challenging things to come.

Rose Bouthillier is Assistant Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland. Her writing has been published in C magazine, frieze, esse, and Art Criticism & Other Short Stories.